This puzzle from Alex Bellos follows the themes in his new book, The Language Lover’s Puzzle Book, which, among other things, looks at number systems in different languages. (See also his Numberphile video.)

This puzzle from Alex Bellos follows the themes in his new book, The Language Lover’s Puzzle Book, which, among other things, looks at number systems in different languages. (See also his Numberphile video.)

“Today is the International Day of the World’s Indigenous People, which aims to raise awareness of issues concerning indigenous communities. Such as, for example, the survival of their languages. According to the Endangered Languages Project, more than 40 per cent of the world’s 7,000 languages are at risk of extinction.

Among the fantastic diversity of the world’s languages is a diversity in counting systems. The following puzzle concerns the number words of Ngkolmpu, a language spoken by about 100 people in New Guinea. (They live in the border area between the Indonesian province of Papua and the country of Papua New Guinea.)

Ngkolmpu-zzle

Here is a list of the first ten cube numbers (i.e. 13, 23, 33, …, 103):

1, 8, 27, 64, 125, 216, 343, 512, 729, 1000.

Below are the same ten numbers when expressed in Ngkolmpu, but listed in random order. Can you match the correct number to the correct expressions?

eser tarumpao yuow ptae eser traowo eser

eser traowo yuow

naempr

naempr ptae eser traowo eser

naempr tarumpao yuow ptae yuow traowo naempr

naempr traowo yempoka

tarumpao

yempoka tarumpao yempoka ptae naempr traowo yempoka

yuow ptae yempoka traowo tampui

yuow tarumpao yempoka ptae naempr traowo yuow

Here’s a hint: this is an arithmetical puzzle as well as a linguistic one. Ngkolmpu does not have a base ten system like English does. In other words, it doesn’t count in tens, hundreds and thousands. Beyond its different base, however, it behaves very regularly.

This puzzle originally appeared in the 2021 UK Linguistics Olympiad, a national competition for schoolchildren that aims to encourage an interest in languages. It was written by Simi Hellsten, a two-time gold medallist at the International Olympiad of Linguistics, who is currently reading maths at Oxford University.”

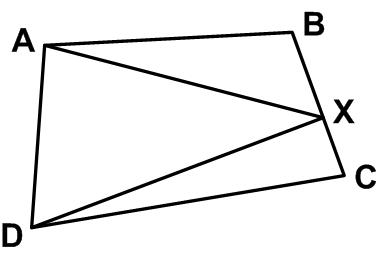

Here is a challenging problem from the Polish Mathematical Olympiads published in 1960.

Here is a challenging problem from the Polish Mathematical Olympiads published in 1960. Here is another Brainteaser from the Quantum magazine.

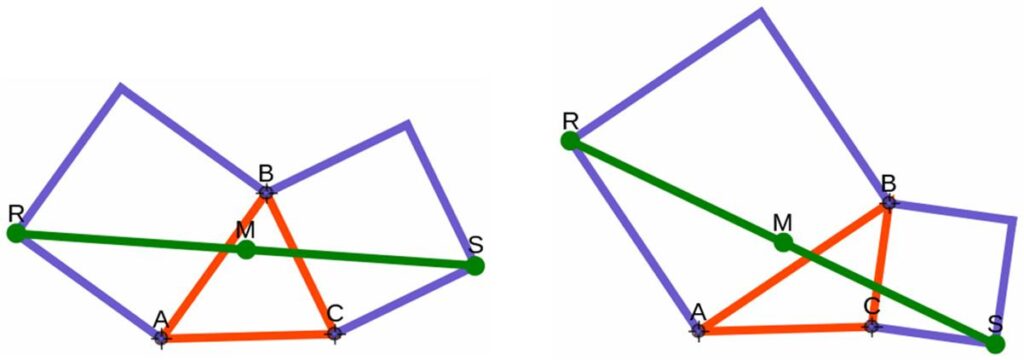

Here is another Brainteaser from the Quantum magazine. This is another simple problem from Five Hundred Mathematical Challenges:

This is another simple problem from Five Hundred Mathematical Challenges: This problem comes from the Scottish Mathematical Council (SMC) Senior Mathematical Challenge of 2008:

This problem comes from the Scottish Mathematical Council (SMC) Senior Mathematical Challenge of 2008: Again we have a puzzle from the Sherlock Holmes puzzle book by Dr. Watson (aka Tim Dedopulos).

Again we have a puzzle from the Sherlock Holmes puzzle book by Dr. Watson (aka Tim Dedopulos). Ian Stewart has a nice logic problem in his Casebook of Mathematical Mysteries, which includes a pastiche of Sherlock Holmes in the form of Herlock Soames and Dr. Watsup, along with brother Spycraft and nemesis Dr. Mogiarty.

Ian Stewart has a nice logic problem in his Casebook of Mathematical Mysteries, which includes a pastiche of Sherlock Holmes in the form of Herlock Soames and Dr. Watsup, along with brother Spycraft and nemesis Dr. Mogiarty.

Here is surprising problem from the 1875 The Analyst

Here is surprising problem from the 1875 The Analyst This is another simple problem from H. E. Dudeney.

This is another simple problem from H. E. Dudeney.