I found an interesting geometric statement in a paper of Glen Van Brummelen cited in the online MAA January 2020 issue of Convergence:

I found an interesting geometric statement in a paper of Glen Van Brummelen cited in the online MAA January 2020 issue of Convergence:

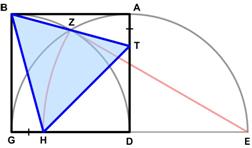

“For instance, Abū’l-Wafā’ describes how to embed an equilateral triangle in a square, as follows: extend the base GD by an equal distance to E. Draw a quarter circle with centre G and radius GB; draw a half circle with centre D and radius DE. The two arcs cross at Z. Then draw an arc with centre E and radius EZ downward, to H. If you draw AT = GH and connect B, H, and T, you will have formed the equilateral triangle.”

So the challenge is to prove this statement regarding yet another fascinating appearance of an equilateral triangle.

See the Triangle of Abū’l-Wafā’

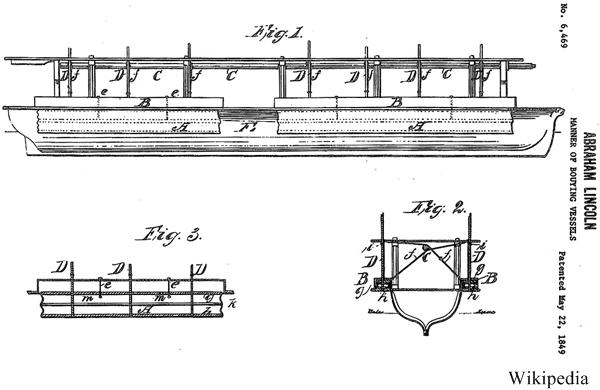

I thought there was nothing new we could learn about Abraham Lincoln, but I see I was quite mistaken after reading Sidney Blumenthal’s

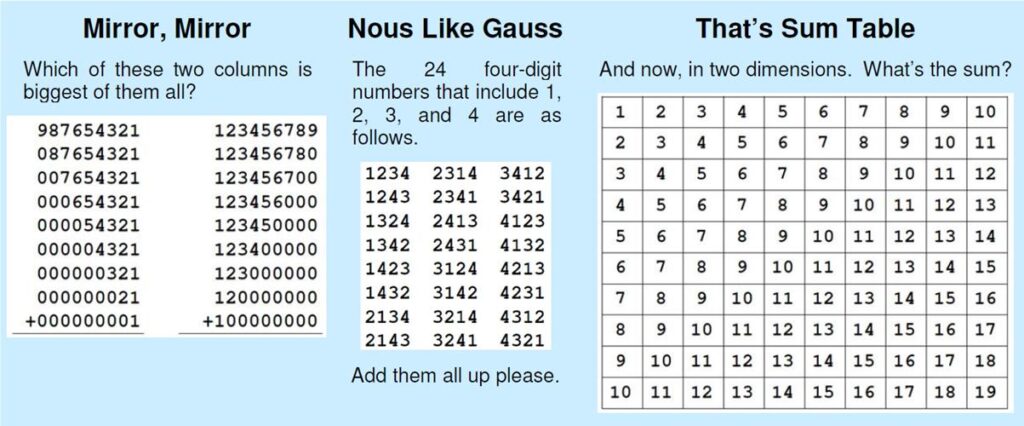

I thought there was nothing new we could learn about Abraham Lincoln, but I see I was quite mistaken after reading Sidney Blumenthal’s  This is another problem from the 2020 Math Calendar.

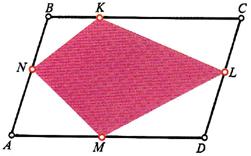

This is another problem from the 2020 Math Calendar. This turned out to be a challenging geometric problem from

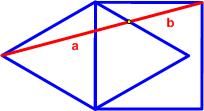

This turned out to be a challenging geometric problem from  Here is another problem from the Quantum magazine, only this time from the “Challenges” section (these are expected to be a bit more difficult than the Brainteasers).

Here is another problem from the Quantum magazine, only this time from the “Challenges” section (these are expected to be a bit more difficult than the Brainteasers).

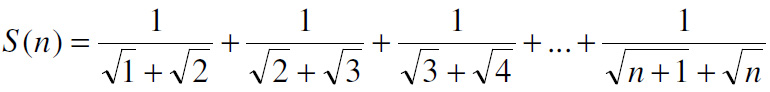

The craziness of manipulating radicals strikes again. This 2006 four-star problem from Colin Hughes at Maths Challenge is really astonishing, though it takes the right key to unlock it.

The craziness of manipulating radicals strikes again. This 2006 four-star problem from Colin Hughes at Maths Challenge is really astonishing, though it takes the right key to unlock it.

Again we have a puzzle from the Sherlock Holmes puzzle book by Dr. Watson (aka Tim Dedopulos).

Again we have a puzzle from the Sherlock Holmes puzzle book by Dr. Watson (aka Tim Dedopulos). This is a cute little problem I came across via

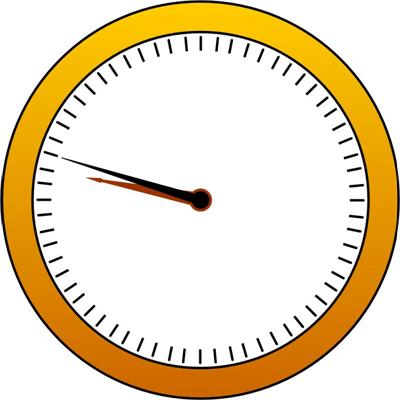

This is a cute little problem I came across via  This is a nice variation on the typical clock problem posed by

This is a nice variation on the typical clock problem posed by