I found an interesting geometric statement in a paper of Glen Van Brummelen cited in the online MAA January 2020 issue of Convergence:

I found an interesting geometric statement in a paper of Glen Van Brummelen cited in the online MAA January 2020 issue of Convergence:

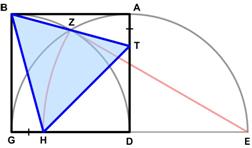

“For instance, Abū’l-Wafā’ describes how to embed an equilateral triangle in a square, as follows: extend the base GD by an equal distance to E. Draw a quarter circle with centre G and radius GB; draw a half circle with centre D and radius DE. The two arcs cross at Z. Then draw an arc with centre E and radius EZ downward, to H. If you draw AT = GH and connect B, H, and T, you will have formed the equilateral triangle.”

So the challenge is to prove this statement regarding yet another fascinating appearance of an equilateral triangle.

See the Triangle of Abū’l-Wafā’

The subtext of this essay might be “word problems,” since the stream of thoughts that led to the za’irajah (zairja) began with a paper I read, while searching for potential problems for this website, on the history of word problems in high school texts in algebra in the 20th and 21st centuries. The following statement by Lorenat caught my attention:

The subtext of this essay might be “word problems,” since the stream of thoughts that led to the za’irajah (zairja) began with a paper I read, while searching for potential problems for this website, on the history of word problems in high school texts in algebra in the 20th and 21st centuries. The following statement by Lorenat caught my attention: There is the famous chicken and the egg problem: If a chicken and a half can lay an egg and a half in a day and a half, how many eggs can three chickens lay in three days? Fibonacci 800 years ago in his book Liber Abaci (1202 AD) did not have exactly this problem (as far as I could find), but he posed its equivalent. And most likely the problem came even earlier from the Arabs. So we can essentially claim Fibonacci (or the Arabs) as the father of the chicken and egg problem. Here are three of Fibonacci’s actual problems:

There is the famous chicken and the egg problem: If a chicken and a half can lay an egg and a half in a day and a half, how many eggs can three chickens lay in three days? Fibonacci 800 years ago in his book Liber Abaci (1202 AD) did not have exactly this problem (as far as I could find), but he posed its equivalent. And most likely the problem came even earlier from the Arabs. So we can essentially claim Fibonacci (or the Arabs) as the father of the chicken and egg problem. Here are three of Fibonacci’s actual problems: I was reading yet another book on the Scientific Revolution when I came across a discussion of the mathematical significance of the invention of perspective for painting in the 15th century Italian Renaissance. The main player in the saga was Leon Battista Alberti (1404 – 1472) and his tome De Pictura (On Painting) (1435-6), which contained the first mathematical presentation of perspective. Even though mathematics was advertised, it was not at the level of trigonometry I used in my post “

I was reading yet another book on the Scientific Revolution when I came across a discussion of the mathematical significance of the invention of perspective for painting in the 15th century Italian Renaissance. The main player in the saga was Leon Battista Alberti (1404 – 1472) and his tome De Pictura (On Painting) (1435-6), which contained the first mathematical presentation of perspective. Even though mathematics was advertised, it was not at the level of trigonometry I used in my post “ An amazing publication was conceived primarily for women at the beginning of the 18th century in 1704 and was called The Ladies’ Diary or Woman’s Almanack. What made it even more remarkable was that each issue contained mathematical problems whose solutions from the readers were provided in the next issue. One particularly sharp woman was Mary Wright (Mrs. Mary Nelson). This is one of her problems:

An amazing publication was conceived primarily for women at the beginning of the 18th century in 1704 and was called The Ladies’ Diary or Woman’s Almanack. What made it even more remarkable was that each issue contained mathematical problems whose solutions from the readers were provided in the next issue. One particularly sharp woman was Mary Wright (Mrs. Mary Nelson). This is one of her problems: It is a bit presumptuous to think I could reduce the universe of mathematics to some succinct essence, but ever since I first saw a column in Martin Gardner’s Scientific American Mathematical Games in 1967, I thought his example illustrated the essential feature of mathematics, or at least one of its principal attributes. And he posed it in a way that would be accessible to anyone. I especially wanted to credit Martin Gardner, since the idea resurfaced recently, uncredited, in some attractive videos by Katie Steckles and James Grime. (This reminds me of the Borges idea that “eighty years of oblivion are perhaps equal to novelty”.) See the

It is a bit presumptuous to think I could reduce the universe of mathematics to some succinct essence, but ever since I first saw a column in Martin Gardner’s Scientific American Mathematical Games in 1967, I thought his example illustrated the essential feature of mathematics, or at least one of its principal attributes. And he posed it in a way that would be accessible to anyone. I especially wanted to credit Martin Gardner, since the idea resurfaced recently, uncredited, in some attractive videos by Katie Steckles and James Grime. (This reminds me of the Borges idea that “eighty years of oblivion are perhaps equal to novelty”.) See the  I have always had a tenuous relationship with the concept of angular momentum, but recently my concerns resurfaced when I did my studies on Kepler, and in particular his

I have always had a tenuous relationship with the concept of angular momentum, but recently my concerns resurfaced when I did my studies on Kepler, and in particular his  Years ago during one of my many excursions into the history of mathematics I wondered how Mercator used logarithms in his map projection (introduced in a 1569 map) when logarithms were not discovered by John Napier (1550-1617) and published in his book Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio until 1614, three years before his death in 1617. The mystery was solved when I read a 1958 book by D. W. Waters which said Edward Wright (1561-1615) in his 1599 book Certaine Errors in Navigation produced his “most important correction, his chart projection, now known as Mercator’s.” Wright did not use logarithms explicitly but rather implicitly through the summing of discrete secants of the latitude as scale factors. But what really caught my attention in the Waters book was this arresting footnote: “Wright explained his projection in terms of a bladder blown up inside a cylinder, a very good analogy.” This article recounts my exploration of this idea. See

Years ago during one of my many excursions into the history of mathematics I wondered how Mercator used logarithms in his map projection (introduced in a 1569 map) when logarithms were not discovered by John Napier (1550-1617) and published in his book Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio until 1614, three years before his death in 1617. The mystery was solved when I read a 1958 book by D. W. Waters which said Edward Wright (1561-1615) in his 1599 book Certaine Errors in Navigation produced his “most important correction, his chart projection, now known as Mercator’s.” Wright did not use logarithms explicitly but rather implicitly through the summing of discrete secants of the latitude as scale factors. But what really caught my attention in the Waters book was this arresting footnote: “Wright explained his projection in terms of a bladder blown up inside a cylinder, a very good analogy.” This article recounts my exploration of this idea. See

I have long been fascinated by Newton’s proof of Kepler’s Equal Areas Law and wanted to write about it. Of course, others have as well, but I wanted to emphasize an aspect of the proof that supported my philosophy of mathematics.

I have long been fascinated by Newton’s proof of Kepler’s Equal Areas Law and wanted to write about it. Of course, others have as well, but I wanted to emphasize an aspect of the proof that supported my philosophy of mathematics. I had been exploring how Kepler originally discovered his first two laws and became fascinated by what he did in his Astronomia Nova (1609), as presented by a number of researchers. Among the writers was A. E. L. Davis. She mentioned that the characterization of the ellipse that Kepler was using was the idea of a “compressed circle,” that is, a circle all of whose points were shrunk vertically by a constant amount towards a fixed diameter of the circle. I did not recall ever hearing this idea before and tried to track down its origin together with a proof — futilely, Davis’s references notwithstanding. I then tried to prove it myself. It was easy to do with analytic geometry. But in the spirit of the Kepler era (before the advent of Fermat’s and Descartes’s beginnings at fusing algebra and geometry) I tried to prove it solely within Euclid’s plane geometry. Some critical steps seemed to come from the great work of Apollonius of Perga (262-190 BC) on Conics. But for me a final elegant proof was not evident until 1822 when Dandelin employed his inscribed spheres. See

I had been exploring how Kepler originally discovered his first two laws and became fascinated by what he did in his Astronomia Nova (1609), as presented by a number of researchers. Among the writers was A. E. L. Davis. She mentioned that the characterization of the ellipse that Kepler was using was the idea of a “compressed circle,” that is, a circle all of whose points were shrunk vertically by a constant amount towards a fixed diameter of the circle. I did not recall ever hearing this idea before and tried to track down its origin together with a proof — futilely, Davis’s references notwithstanding. I then tried to prove it myself. It was easy to do with analytic geometry. But in the spirit of the Kepler era (before the advent of Fermat’s and Descartes’s beginnings at fusing algebra and geometry) I tried to prove it solely within Euclid’s plane geometry. Some critical steps seemed to come from the great work of Apollonius of Perga (262-190 BC) on Conics. But for me a final elegant proof was not evident until 1822 when Dandelin employed his inscribed spheres. See